Living in Singapore, a nation recently labelled as livingthrough a "Scamdemic" by the Financial Times, my phone has become abattleground. I receive anywhere from five to ten calls a week from unknownnumbers. Like most residents here, I have developed a reflex where I simply donot answer if I do not know the number.

Last Friday, however, I broke my own rule.

Having just finished work, curiosity got the better of me. I picked up a FaceTime audio call from an unknown caller because I wanted to see what the latest script was. I thought I might waste fifteen minutes of their time so they could not harass someone more vulnerable. When the scammer finally realized I was playing the victim and hung up, he angrily complained that I had wasted his time.

I put the phone down expecting to feel a sense of minor victory, but instead, I was left with a profoundly weird feeling. Yes, I had tied up a scammer's time. However, there was a very high probability that the person I had just provoked was not a willing criminal. He was likely a victim of human trafficking operating under duress.

It was a stark reminder that we do not talk enough about the "supply side" of this global crisis.

The Trillion-Dollar "United Republic of Scams"

The scale of the scam industry is almost incomprehensible. According to GASA, international scammers steal over $1 trillion per year.

To put that in perspective, that figure eclipses the entire global airline industry which was valued at $996 billion in 2024. If scamming were a country, specifically the "United Republic of Scams", its GDP of $1.03 trillion would make it the 17th or 18th largest economy in the world.

While AI is poised to automate parts of this illicit industry, scams today still require significant human manpower. Unfortunately, that manpower is coming from a terrifying source.

Trafficking for Forced Criminality

A UN report estimates that hundreds of thousands of people have been trafficked into online scam compounds across Southeast Asia. There are around 120,000 in Myanmar and 100,000 in Cambodia alone.

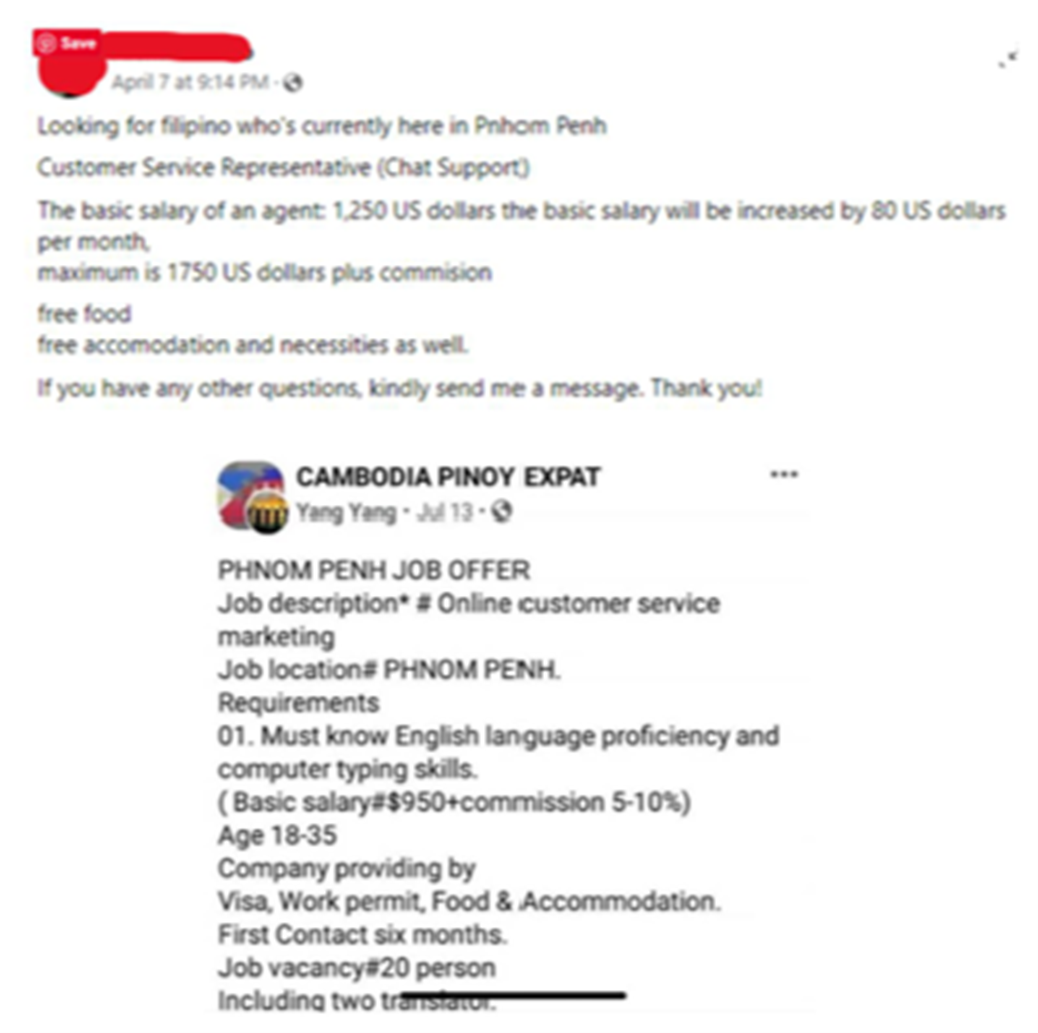

The modus operandi is cruelly simple. People are lured by advertisements promising simple jobs with high salaries. Once they arrive, their passports are confiscated. They are trapped in what human rights organizations now describe as "trafficking for forced criminality.

These places are not call centers. They are cybercrime forced labor camps. Inside, people often work 12 to 16 hour days under armed guard. They face beatings and torture if they miss their financial targets.

We must face a hard truth regarding the scam industry. It has two sets of victims: those pressed to send money to the wrong account, and those being violently pressed to convince them to do so.

Shifting the Focus from Demand to Supply

For years, governments, regulators, and the financialindustry have focused almost exclusively on the "demand side" ofscams. They have tried to protect the end consumer through various methods:

- Educating consumers on red flags.

- Mandating "Confirmation of Payee" to verify account names before transfers.

- Implementing "cooling off" periods for high risk transactions.

- Facilitating tighter data sharing between banks and law enforcement to identify mule accounts.

- Shifting liability burdens onto banks.

While everything done to protect customers helps, we know there is no silver bullet on the demand side alone. Fortunately, what is changing now is that some governments and organizations are finally going after the supply side. They are targeting the industrial scale scam factories behind the screens.

We are seeing unprecedented action against theinfrastructure of fraud:

- Physical Raids: In Myanmar, military raids on infamous hubs like KK Park and sites around Shwe Kokko have led to the detention of thousands of people. This has significantly disrupted operations. China is also visibly pushing its neighbors to take action, as many victims on both sides of the phone are Chinese nationals.

- Tech Disruption: The private sector is stepping up. SpaceX recently announced it cut Starlink satellite communication links to more than 2,500 terminals used by scam compounds in Myanmar. This effectively severed their lifeline to the internet.

- Targeting the Kingpins: The real criminals are those designing the scripts and laundering the money. Western countries are finally hitting them where it hurts. Recently, Chen Zhi, who has long been suspected of orchestrating large scale scam centers in Cambodia, was hit by sweeping US and UK sanctions as well as a US indictment.

- Following the Money: The financial seizures are staggering. The Singapore Police Force seized over S$150 million connected to Zhi’s network. Concurrently, the US Department of Justice announced its largest forfeiture action in history by seizing approximately $15 billion in Bitcoin identified as proceeds of Zhi’s criminal schemes.

Conclusion

Stopping fraud isn’t just about protecting consumers. It’s about reducing the incentives that lead people to be trafficked into becoming scammers.

This is where solutions like iPiD and KYP (Know Your Payee) play a pivotal role beyond simple fraud prevention. When we successfully fight the demand side by blocking payments to scammers, we directly impact the supply side. By making it harder for these criminal enterprises to succeed, we lower their return on investment.

If we can use tools like KYP and others to render these scams unprofitable, we reduce the economic incentive for syndicates to run these camps in the first place. Fighting the demand side is, therefore, a direct way to fight human trafficking. We need to keep up the pressure on all fronts, including the supply-side.